សួស្តី! នេះជាប្លុកដំបូងរបស់នាងខ្ញុំដែលមិនធ្លាប់មាន។ នាងខ្ញុំសុំទោសប្រើពាក្យច្រើនពេក។ នាងខ្ញុំសន្យាចែករំលែកការស្រាវជ្រាវនិងបទពិសោធន៍នៅកម្ពុជា។ ដំបូងអំពីជីវិតរបស់នាងខ្ញុំនៅក្នុងប្រទេសកំណើតរបស់នាងខ្ញុំ។

នាងខ្ញុំឈ្មោះអ៊ីសាបេឡាមកពីប្រទេសអាមេរិក។

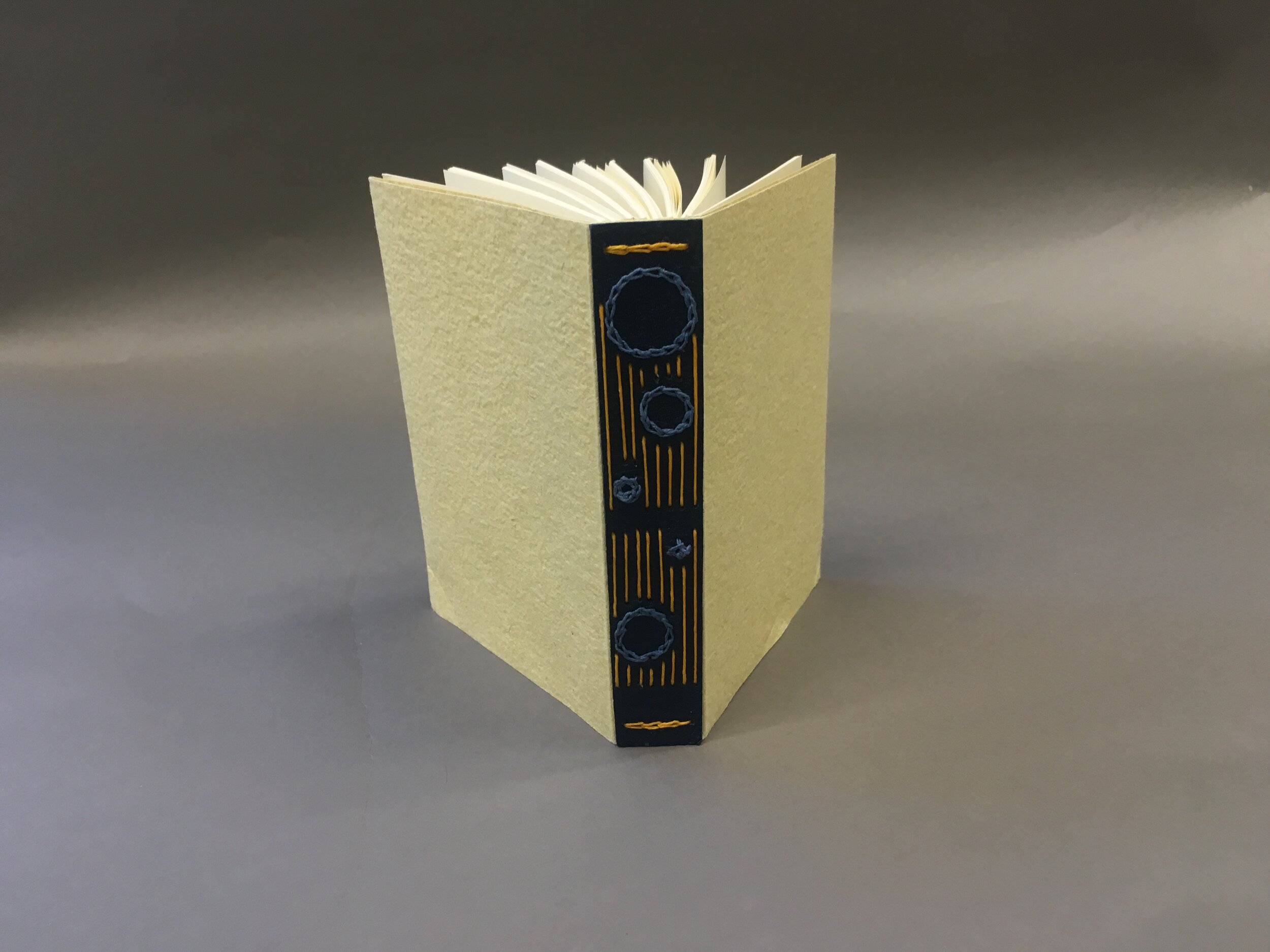

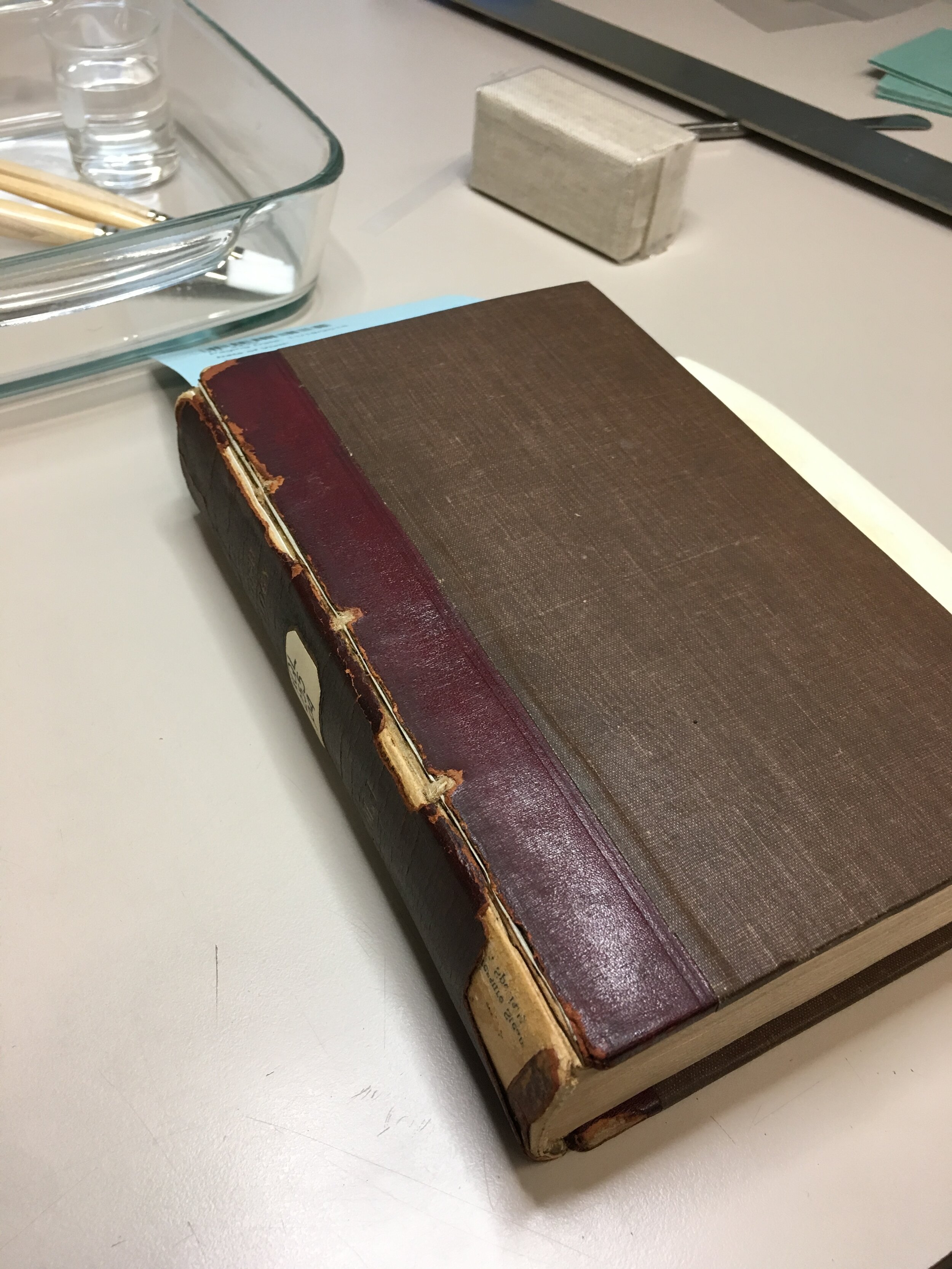

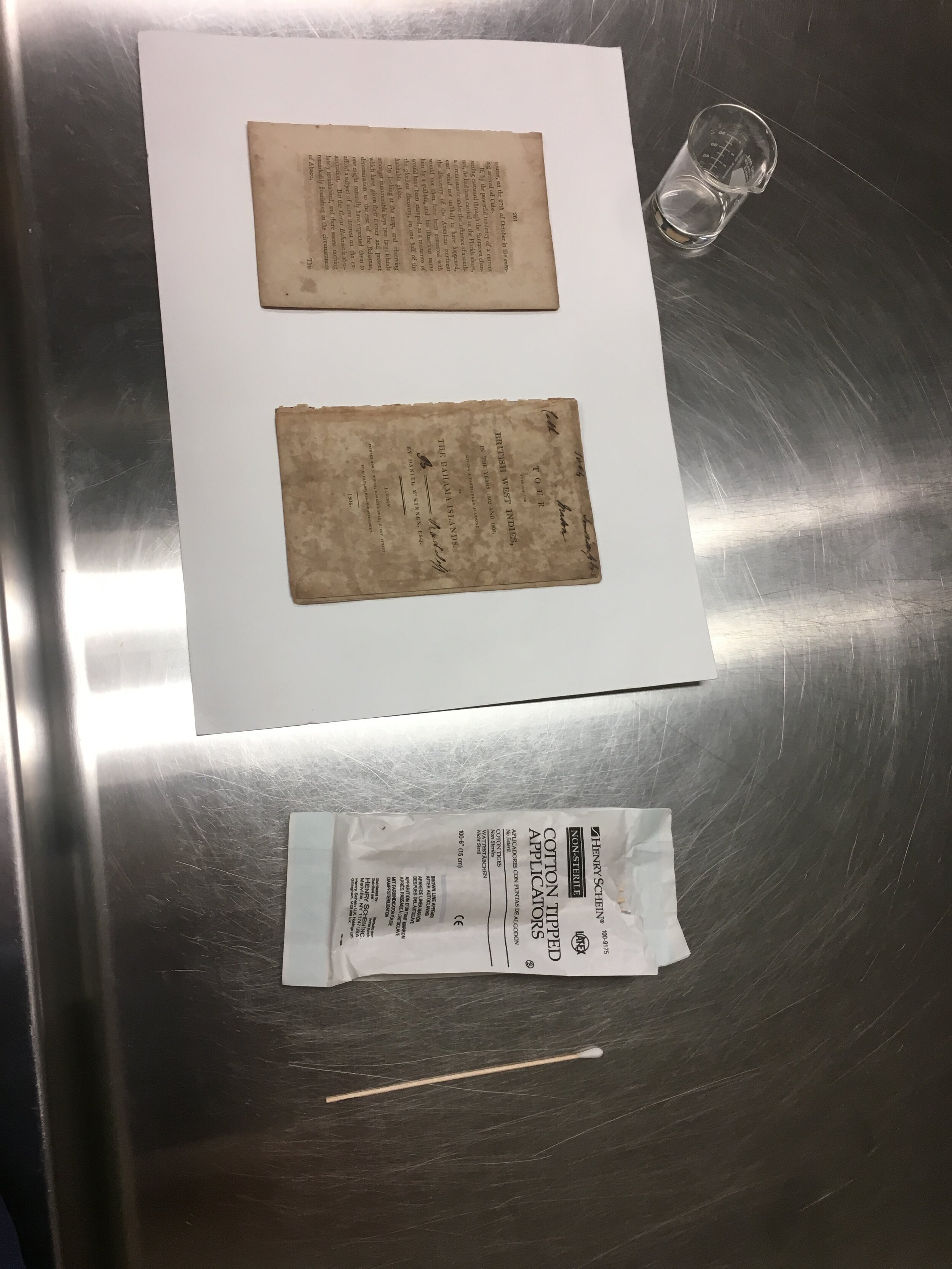

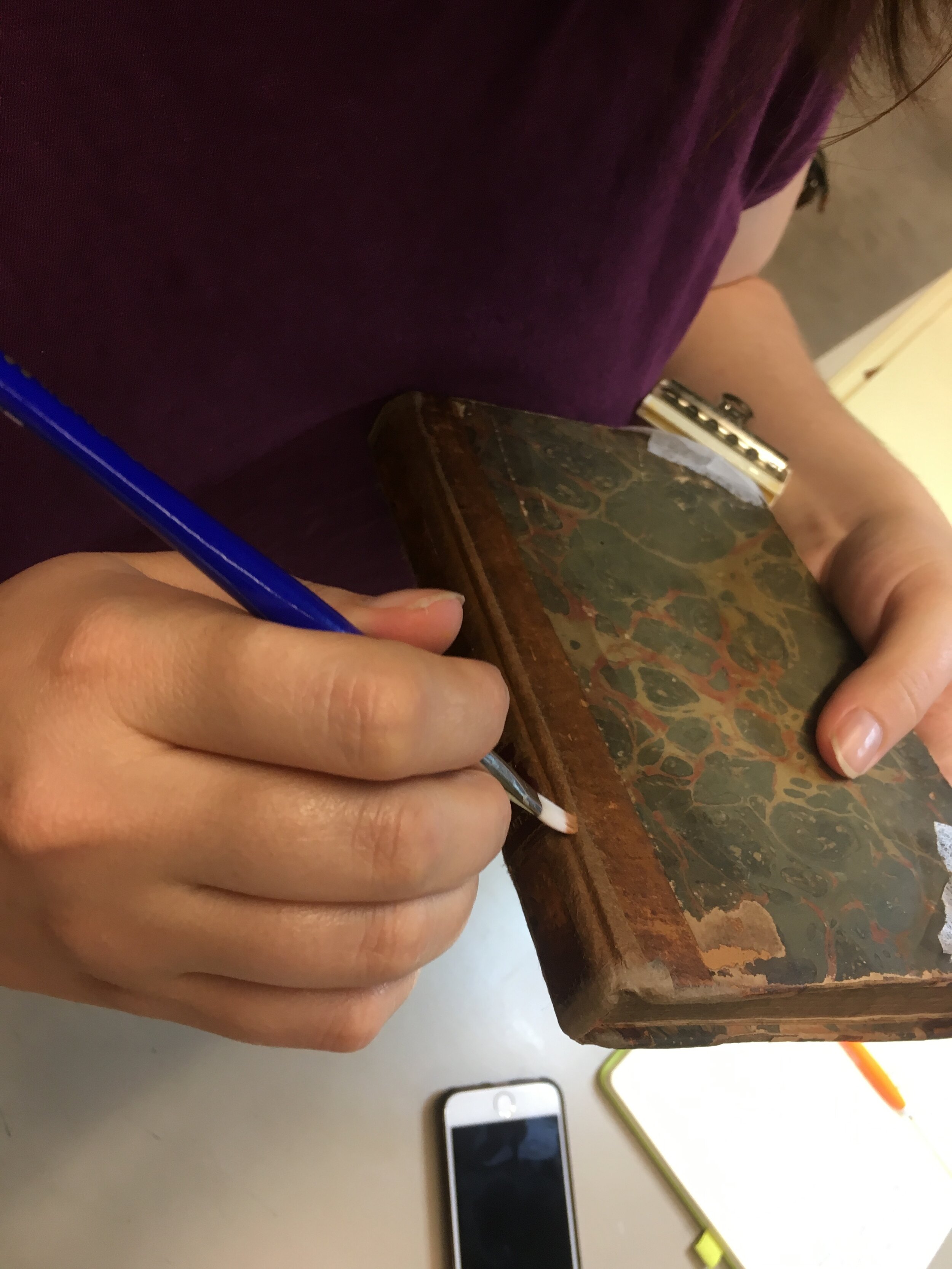

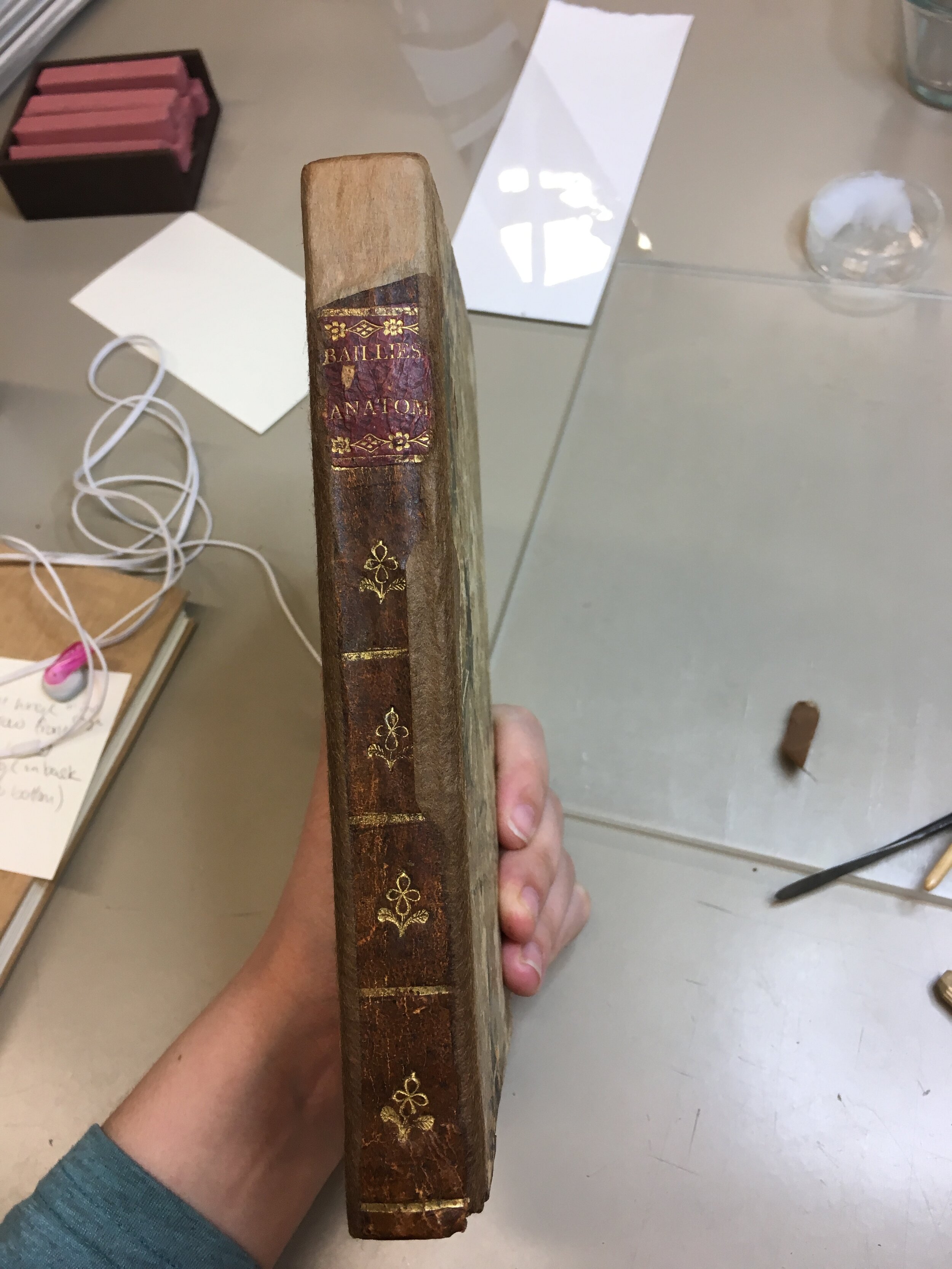

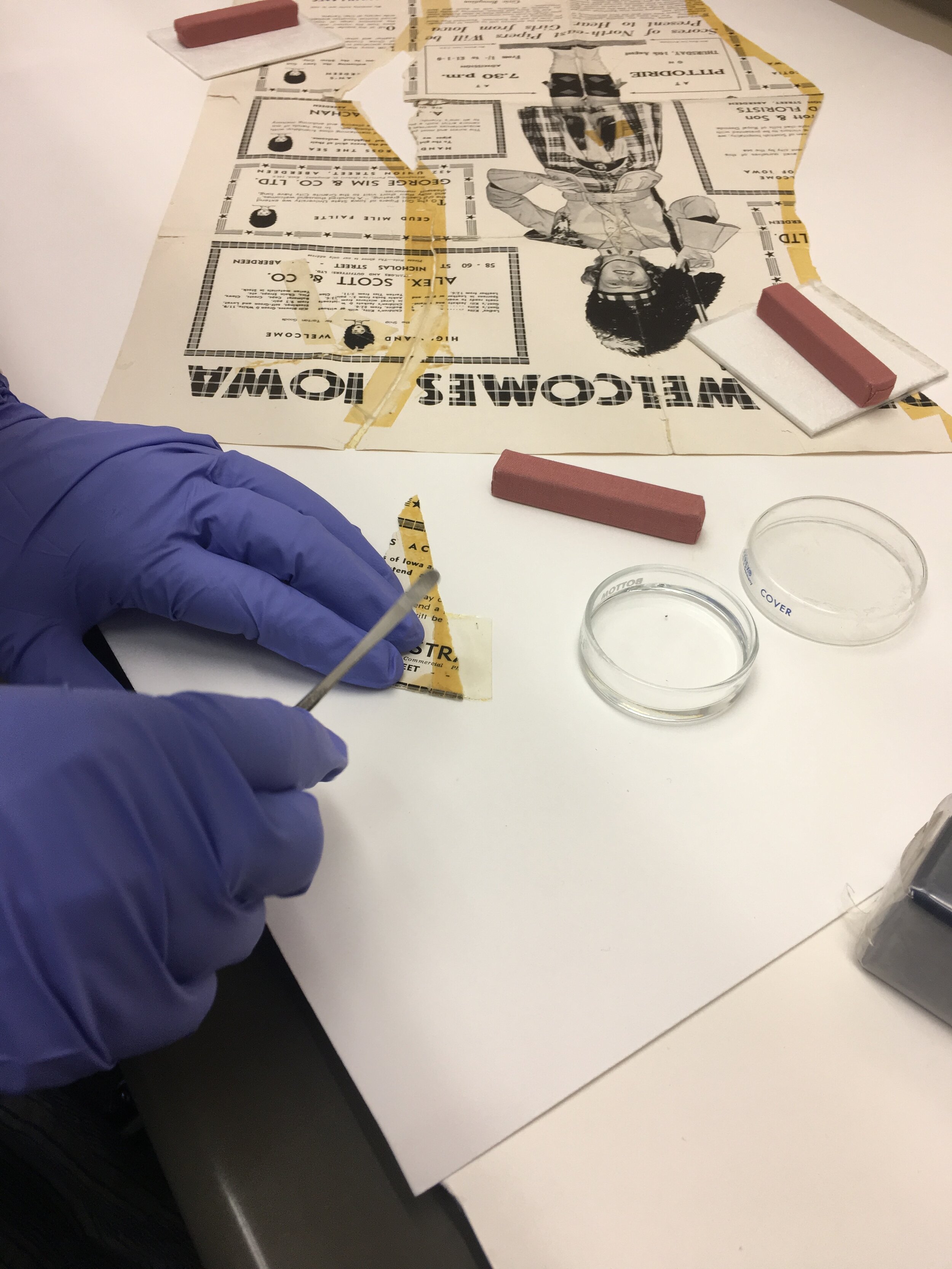

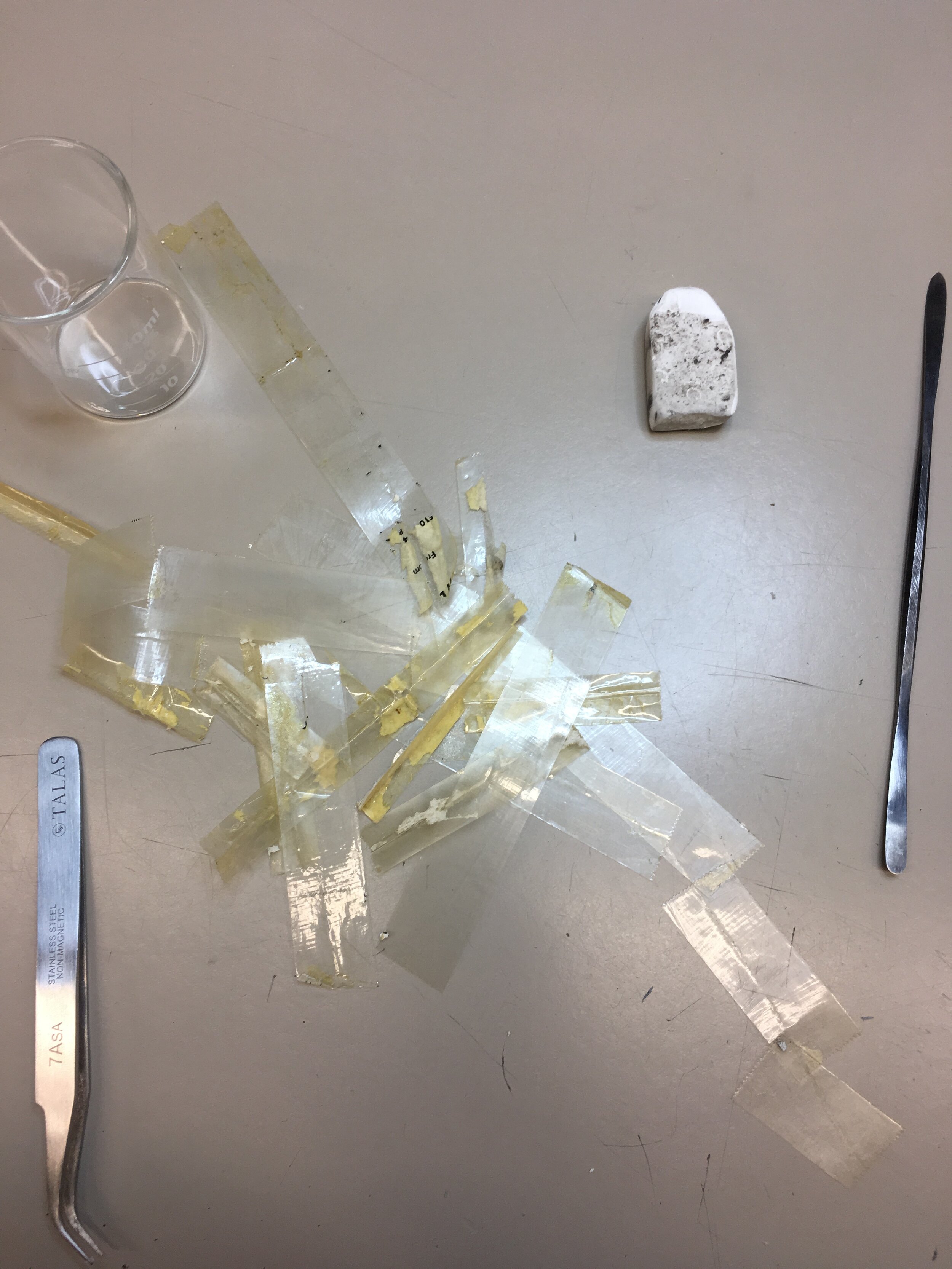

នាងខ្ញុំបញ្ចប់ការសិក្សាពីសកលវិទ្យាល័យនៃសកលវិទ្យាល័យIowa អូវ៉ាសម្រាប់សៀវភៅនៅខែឧសភាឆ្នាំ ២០១៩ ដោយមានMFAក្នុងការបង្កើតសៀវភៅក្រដាសនិងបោះពុម្ព។វាជាកម្មវិធីរយៈពេល ៣ ឆ្នាំដែលនាងខ្ញុំរៀនធ្វើអ្វីៗគ្រប់យ៉ាងដោយដៃ។ នាងខ្ញុំធ្វើការនៅមន្ទីរពិសោធន៍សៀវភៅនិងអភិរក្សក្រដាសនៅសាកលវិទ្យាល័យក្រោមការដឹកនាំរបស់ Giselle Simon, Elizabeth Stone, និង Candida Pagan ។

កាលពីរដូវក្តៅមុនខ្ញុំទទួលបានជំនួយពីរ។ ដើម្បីរៀនអំពីក្រាំងព្រះពុទ្ធសាសនាខ្មែរ។ ហើយដើម្បីរៀនភាសាខ្មែរនៅមជ្ឈមណ្ឌលសិក្សាខ្មែរ (CKS) នៅភ្នំពេញ។ យើងបានទៅទស្សនាខេត្តជាច្រើនហើយបានស្វែងយល់អំពីវប្បធម៌ខ្មែរ។ អរគុណ CKS ដែលបានណែនាំអំពីប្រទេសកម្ពុជានិងភាសាខ្មែរ។ បើគ្មាន CKS ខ្ញុំមិនស្គាល់អ្វីទាំងអស់។

Hello world! This is my first blog ever, so my apologies if it’s a little clunky at first. I promised many people in the United States that I would stay connected and update with my research findings and overall adaptation to living in a new country. First I will give a little background and detail what my life was like before I moved to Cambodia. If you already know me, skip to the next post!

My name is Isabella Myers, I recently graduated from the University of Iowa Center for the Book in May of 2019 with a Masters of Fine Arts and a focus in artists’ books, papermaking, and letterpress printing. It was a three year program where I learned how to make almost everything entirely by hand. I also had the distinct pleasure to work in the UI Library’s Book and Paper Conservation Lab under the direction of Conservator Giselle Simon, Assistant Conservator Elizabeth Stone, and Project Conservator Candida Pagan.

Last summer, I was awarded two grants. One was from the UI Graduate College to begin an inquiry into Cambodian Buddhist manuscripts made from handmade paper, these manuscripts are called kraing. The second was as a Khmer language fellow with the Center for Khmer Studies (CKS). When I write Cambodia, I am referring to the country, and when I write Khmer when I refer to its people and the primary language spoken in the country. Anyway, I was awarded a six-week language intensive course on Khmer language and culture based in Phnom Penh, Cambodia’s capital. We also took a number of field trips all around different areas of the Cambodian countryside. I am eternally grateful to CKS for this introduction to the country and the Khmer language. Without this course, it’s hard to say where I would be.

People often ask me: why Cambodia? Especially because researching paper manuscripts would certainly be easier in a place like Thailand where there are national collections that are much more detailed in documentation, or in a country like Laos where these manuscripts are still being produced in the traditional way. But Cambodia was calling to me. And I answered the call! In the weeks before traveling to Cambodia in summer 2018, I spent a lot of time googling “what does Cambodia look like?” Trying to memorize the names of popular food items in Khmer according to Wikipedia and Youtube vloggers. I was so nervous, I was opening Pandora’s box!

And then, I took the leap and I’m glad I did. First of all, the Khmer people are more welcoming than I could ever imagine. I found myself trying simple Khmer phrases in the markets and impressing the locals. I was meeting new friends in all kinds of places: outside of a pagoda, at the corner store, on a train, at Angkor Wat, etc. I was trying the food and CKS was even teaching us how to cook some Khmer dishes. I discovered that Khmer pineapple is amazing. I loved a snack called chekchien ចេកចៀន or fried banana. My favorite was something I had never seen before: mangosteen. I was learning phrases that made Khmer people laugh like mekh kampoung phlieng haey មេឃកំពុងកៀងហើយ or the sky is already raining, a bit of an inside joke because it’s a popular song here. But also great banter for rainy season, when I was visiting.

When you hear ‘monsoon season,’ it sounds a little scary. But I learned to embrace the rain. I learned to read the sky and know approximately how much time I had to make it home before it would get bad. I rode my bicycle in the busy chaotic streets of Phnom Penh and it made me feel like I was back in Chicago again. But it was friendlier. I narrowly avoided many crashes, but Khmer people love smiles. I would flash a smile at the person with whom I almost collided and they would return the smile. People often asked me if I was homesick, but the truth was Cambodia was starting to feel like home.

The language program was so intense I had little time to explore my research inquiry: kraing. It turns out that kraing are very rare, an estimated 2% survive in the nation. I found a very useful dissertation written by Dr. Trent Walker, an incredible American scholar from University of California Berkeley. He detailed the location of some of the few remaining kraing in Cambodia. It was not guaranteed that any of these manuscripts were still in the attributed locations, however, because they had been catalogued years back. I asked a friend I met outside of a pagoda if he would like to accompany me on the journey to a pagoda in Kampong Cham Province to confirm that there were still kraing there. My friend is a former monk and he was very interested in my project and also spoke nearly perfect English. It was a good fit, so together we went to the pagoda to see about some manuscripts.

And they were there! I couldn’t believe it. My heart was racing. With only a couple weeks left in the country, I knew my work here had only just begun. Once I returned to the US, I started writing what became my Fulbright grant proposal. A three-tiered project to preserve and document kraing and to share my findings with the Cambodian public and the international Book Arts community, to put Cambodia on the map of the global spread of paper technology, securing its rightful place in this complex and fascinating discourse surrounding hand papermaking.

It wasn’t exactly an easy task in my final thesis year of graduate school. I did it though! And then I waited for months and months to hear back. When I received notification that my proposal had been selected for a Fulbright grant, it felt like a dream. Even sitting here writing this in the Cambodian countryside, I still feel like I am dreaming. It’s very important to me to document my research and life in Cambodia thoroughly so I have created this small space on the worldwide web to share with the public this exciting adventure in the Kingdom of Wonder. Afterall, one of the tenets of the Fulbright program is to promote mutual understanding across cultures. Eventually I would like to include a translation into Khmer to share with my host family and friends in the village. I invite any suggestions from native Khmer speakers in the comments if I mistranslate anything.

And a picture is worth a thousand words so here are some photos from my life before Fulbright. You can click on each photo to enlarge it!